Saving soul after soul after soul ...

- deansimpson7

- Sep 5, 2025

- 4 min read

BY CAPTAIN PAUL FARTHING*

The Salvation Army’s first 10 years in Australia were a wondrous success. Take, for instance, their efforts in NSW.

The Army arrived in Sydney in December of 1882 when Thomas and Adelaide Sutherland, Australia’s first Salvation Army officers, ‘opened fire’ in Paddy’s Markets, Haymarket.

Just over eight years later, a census found that 0.915 per cent of adults in NSW identified as Salvationists. This number is astounding when one considers that, as a new religion, The Salvation Army had no nominal members, and anyone who claimed to be a Salvationist was likely to be an active member.

The same census found that 2.13 per cent of children in NSW attended a Salvation Army Sunday school. In that same period, the Army established 99 official meeting places in NSW and many more outposts. Salvation Army evangelism was extraordinary.

A report to the War Cry from the Sydney Corps shows the kind of spiritual impact the Salvation Army was having on the state:

Monday – At the Railway Station. Good meeting. Three Saved.

Tuesday – Soldiers Class. Some red-hot testimonies.

Wednesday – Paddy’s Market Open Air. The people howled at the Salvationists, but the Salvationists were willing to suffer their hatred for Christ’s sake. Four Saved.

Saturday – York St meeting. Devil was routed out of five souls.

Sunday – 7am Knee Drill, one saved. 11am holiness meeting, Spirit broke out and everyone fell to their knees and prayed. 5pm Evening Open Air meeting followed by meeting in the Protestant hall, five saved. Nineteen souls for the week.

This type of report was not uncommon; hundreds of souls were being saved through Salvation Army gatherings every week.

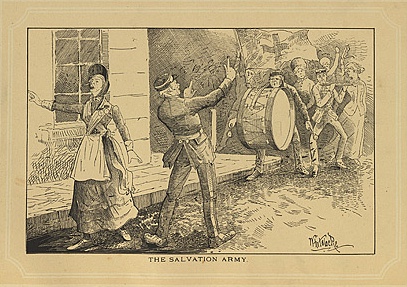

By 1883, Salvos (left) were being portrayed as loud and aggressive on the streets of Sydney (image: State Library of NSW). The evangelical approach of early Salvos became a common sight on Sydney streets in the 1880s (image: National Gallery of Australia).

Now, one could read this and assume that the early Salvation Army saved souls because evangelism in the 1880s was easy. “People back then”, one might say, “were more willing to hear and believe the church’s message”. But while these most surely were different times, it would be a serious mistake to think that evangelism in the 1880s was easy.

In his book, Defending a Christian Country, the historian Walter Phillips describes the 1880s as an especially difficult time for the church. Secularism was on the rise. The NSW Government abolished state aid to churches and, in doing so, confirmed the separation of church and state.

Museums and libraries were open for the first time on a Sunday, providing competition for churches. Secularist lecturers made enthusiastic attacks on Christianity to full halls.

Darwin’s The Origin of the Species (1859) was well known by the 1880s, and according to esteemed historians Stuart Piggin and Robert Linder, the questions it raised made it “increasingly difficult to save souls”.

Church attendance in most Protestant denominations was in decline. In 1882, the Chairman of the Congregational Union in NSW, J.F. Cullen, made the logical point that if saving people was easy, the established churches would already be doing it, and The Salvation Army would have had no cause to exist! These were not ‘easy’ times.

Furthermore, Salvationists refused to take the easy road to building a church. They went for unsaved souls, and they really did go for the worst, to paraphrase a famous William Booth quote.

The first meeting held in NSW was largely attended by churchgoers, Christians who had come to scope out this strange new movement. This enraged a certain Captain Alex Canty. He took to the pulpit in a fury, berating the congregation for their respectability: these were not the sort the Army wanted, he ranted.

Adelaide Sutherland warned the congregation against leaving their churches to join the Army unless they were willing to fight the battle for souls. Joining the Army, she said, would be like “jumping out of the frying pan into the fire”.

The Army decided to hold its meetings at the same time as the other churches to ensure that it only attracted non-churchgoers. This move was a success, and by the end of the year, the Australian Town and Country Journal described the Army congregation as a “class of people who under no circumstances whatsoever attend the services of the church”.

At the opening of the Newtown Barracks, the local mayor said that “The Army had accomplished what other organisations had failed to do. They had taken the Scriptures to the fallen and been the means of raising them up.” The theme of 1880s commentary on the NSW Salvation Army is that by saving the “unreflecting, the unwashed, the untutored classes”, The Salvation Army had done the impossible. These were not easy times.

We must also remember that the early Salvation Army experienced actual persecution. Meetings were attacked by larrikins, Salvationists were thrown into jail for marching without permit, readers wrote frequent letters of bitter complaint to their local newspaper.

Stories of Salvationists being attacked by the ‘Skeleton Army’ or thrown into jail by overzealous policemen have been reframed as heroic, as if it were all part of the adventure. But a night in the cells after being verbally abused and pelted with fireworks could not have seemed all that wonderful at the time.

These, I say again, were not easy times. Yet despite all this opposition, The Salvation Army saved soul after soul after soul.

The lesson is this. Evangelism isn’t easy right now, but it wasn’t easy back then either. The Salvation Army saved thousands back then, and we can do it again now.

*Captain Paul Farthing is the Corps Officer at Shellharbour on the NSW South Coast