Remember the Sabbath?

- deansimpson7

- Aug 17, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 18, 2025

BY ANTHONY CASTLE

What day is it?

It’s a question I hear often. My children ask it most mornings, as if they don’t recall the day before. I understand what they need to know, though: Do I put my school clothes on? Is it the weekend? The question they are really asking of me is ‘Where are we in life right now?’

It can be an annoying question during the early-morning routine. I’d rather they remember it for themselves, but it’s annoying for another reason; I can’t always answer. I stop to remember this basic fact, and for the small time in which I can’t, I feel lost.

There are explanations for this temporary amnesia – the pre-coffee haze, or whatever the paternal equivalent of ‘mum brain’ might be. Memory loss is common in middle age, but I feel as if it’s getting worse. I don’t seem to remember things like I used to, and I’m not alone.

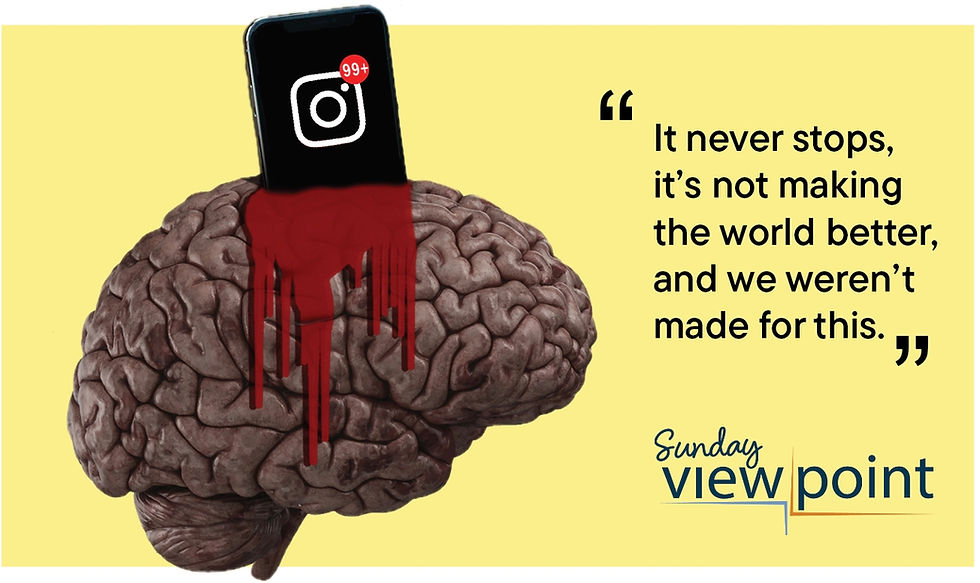

‘Brain rot’ was the Oxford Word of the Year in 2024, a term that has come to describe a common sense of fading intelligence. Increasing numbers of adults have reported symptoms of brain fog in recent years. Speaking with friends, I came to realise it’s not just the day that might be briefly forgotten, but tasks or current events. I have come to call this ‘the forgetting’: a feeling of being lost, overwhelmed by it all. More and more, we are asking, How did we lose track of things? How do we get back to normal? How do we stop this?

Research indicates attention spans have shrunk by more than half in the last 20 years. There are health reasons for the trend of cognitive decline, such as the effects of long COVID, or increasing life expectancies, though technology is often blamed.

Research has found that memory is reduced in adults who multitask across multimedia technologies, particularly in workplaces. Moving from task to task, screen to screen, creates a unrecognised mental exertion known as ‘switch cost’. This ‘switch cost’ has crept into our personal lives, too, with specialists coining the term ‘digital dementia’ to highlight the memory loss associated with overuse of smartphones.

While there have always been social panics about new forms of technology, from television to video games, studies have found that social media can affect focus. Twenty minutes on TikTok can significantly decrease the attention span and memory of its young users, and even increase the likelihood of cognitive decline in adulthood.

There have been some attempts to stop the brain rot created by work and smartphones, with new ‘right to disconnect’ laws giving workers the right to log off after hours, and schools banning phones for students. Similarly, the government’s social media ban is designed to keep young people off these platforms entirely, though experts question whether the ban will be effective.

“We have built a new, digitised world that we aren’t really made for.”

Each of these measures may limit the reach of technology in our work lives and personal lives, but they cannot stop it. We buy movie tickets, read the news, talk to teachers, organise weddings, do banking – do anything – through digital interfaces. We have fully digitised society. Jobs, media, our communities – all are now online.

We have lost track of things because things have changed. We may not be able to get back to normal, as this might become the new normal. I wonder if the reason we can feel so lost is because we are. We have built a new, digitised world that we aren’t really made for.

I find myself deleting social media apps from my smartphone from time to time, making spaces to leave the device at night. Research finds that social media breaks can improve mental health, but I have wondered about the degree to which it should be routine, part of the week even.

The rest is up to us

There is a time in Scripture known as the Sabbath, meaning to stop. The Sabbath is a weekly day of rest in religious life, observed differently in different traditions. A Sabbath time could be practised weekly, or even for a year. During Sabbath times, people rested, the fields grew wild for the poor and the migrant to eat from, debts were cancelled, and slaves were released.

The idea has its origins in the Biblical creation story (Genesis 1), and points to rest being a necessary rhythm in the divine, in the natural world, and in the human condition. Stopping is sacred, and rhythms of rest make the world. Creation and recreation are connected.

This new digital world was made for us to lose ourselves in, to increase our addiction, our screen time. Politicians deliberately ‘flood the zone’ with misinformation to confuse. Social media platforms have admitted they are susceptible to disinformation campaigns. It never stops, it’s not making the world better, and we weren’t made for this.

Each day, the average Australian checks their email 77 times and spends three hours on their smartphone. We cannot stop the digitisation of society, but we can find time to stop, to rest. We can make space – from work, from social media, from smartphones, from the noise made by the powerful. These platforms rely on screen addiction to gather our data and sell it for hundreds of billions of dollars.

So, unless we choose how to use these things, these things will continue to use us. There are no easy answers to this new, digitised world, but unless we develop regular routines to remember where we are in life, then we will continue to feel lost.

I won’t always remember what day it is in the early hours, but we need to remember to practise Sabbath in our lives. We can choose to stop, and rest in what is sacred, not rotting but growing, connecting to what makes the world around us better.